Playing open guard is hard, especially when facing a fast, athletic outside passer who will try to move from side to side, making you extremely tired in order to get the guard pass.

When we don’t know what to do in a difficult situation, I believe our focus should be on identifying the problems preventing us from doing what we want.

The main problem here is mobility, and the solution is connection. If we can connect with this athletic guard passer, we can slow him down and set up our attacks.

However, it’s difficult to establish an initial connection in no-gi from an open guard scenario. The usual advice is to play a seated guard, which allows for easier connection. I believe this is great advice. The problem is, a good opponent can still force us onto our back and flank us. Also, a seated guard leaves you vulnerable to body lock passing. Depending on who you're fighting, you may not want to be in a seated posture when playing open guard.

Whether we choose to play supine or are forced to, we will face the problem of connection from this position. Your arms are farther away from your opponent, and you have less mobility than when seated. As a result, the supine guard is relatively easy to outflank and pass.

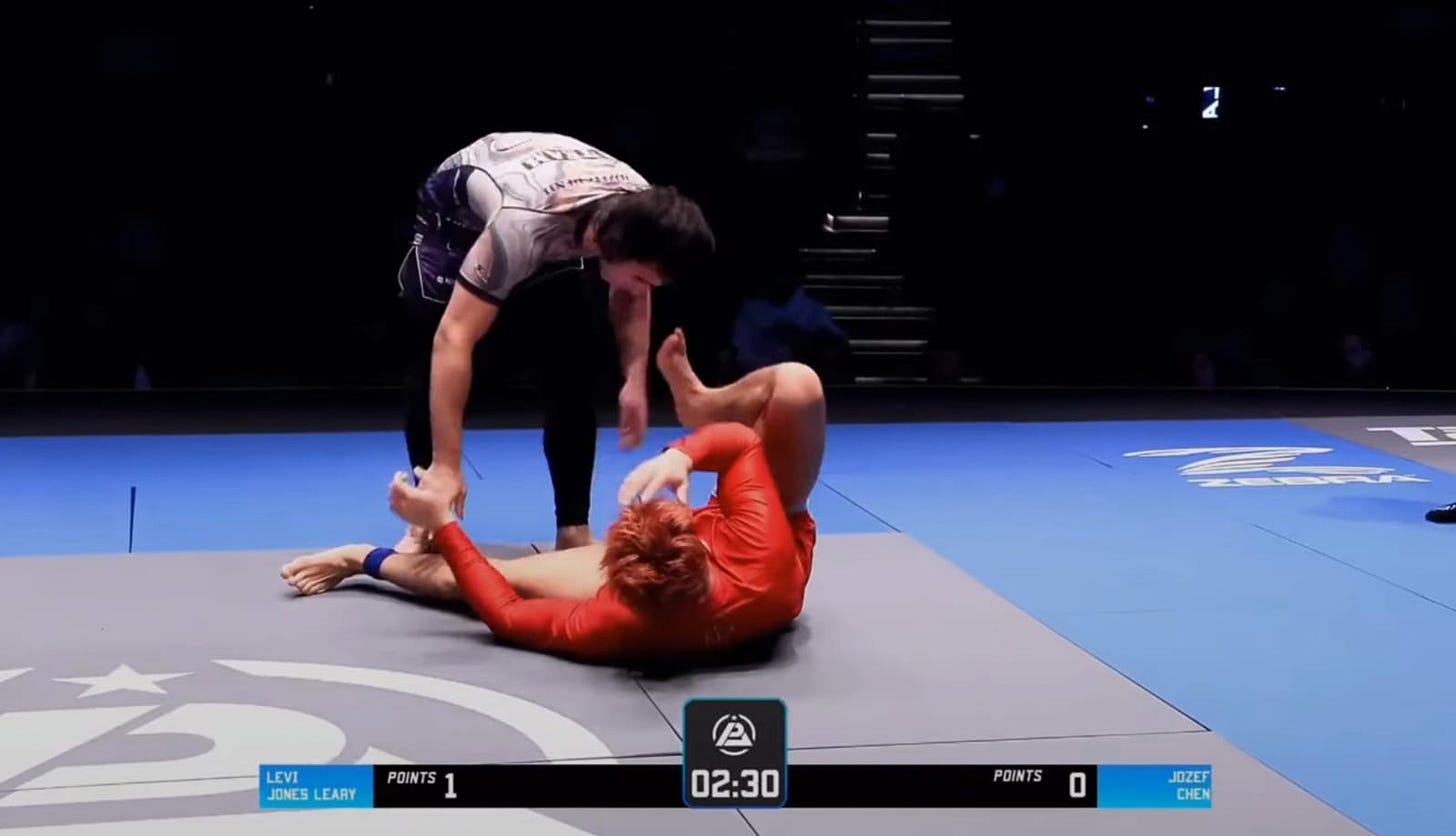

However, there are outliers who have demonstrated the effectiveness of playing the supine guard. Among them are: Mikey Musumeci, Lachlan Giles, Diego Pato, and Levi Jones Leary (probably the one I have studied the most). They have all been able to play a supine guard effectively, using their retention to connect with their opponents.

Recently, I’ve been applying what I learned from them to my game. As a result, I could see my supine guard improving day after day. I already had a decent ability to retain my guard, but I realized that the way I did it used to let me open for good outside passers to switch side to side on me. I never noticed this before because I usually play seated, and I can connect pretty quickly from there. However, after realizing this, I made improving my supine guard a priority.

That’s why I’m here today: to share my findings with you and help you develop an effective, dangerous supine open guard. So, let's dive in.

Understanding The Main Problems — Avoid The High Leg

As I mentioned earlier, the problem with the supine guard is that it’s difficult to establish a significant connection with your opponent before he creates an angle and starts camping.

Before they settle into the camping position, we can throw a high leg with our far leg to stop them from moving in that direction. That's usually what you're supposed to do in that scenario, and what I always did. The problem with that is that, when your opponent has a strong angle on you, the high leg has to be big enough to avoid the pass. This gives the passer the opportunity to get a cross-scoop grip on that leg and either long-step on the same side or duck under on the other side.

Good outside passers want you to throw an exaggerated high leg so they can get a scoop grip and possibly switch sides. In my opinion, this makes the traditional high leg a bad option for guard retention against a skilled, athletic opponent.

Therefore, we need an alternative to the high leg that allows us to kill the angle our opponent just created and gives us an opportunity to connect and attack.

Near Side & Far Side

A traditional high leg against a strong angle usually results in your foot ending up on the far side of your opponent’s body. This allows your opponent to take the cross scoop grip. Since we've already established that we want to avoid that, what can we do?

The advantage of connecting with your leg on the far side is that your opponent can’t move in that direction anymore, which completely kills the angle. If you connect to the near side instead, your opponent can theoretically keep moving, but you should be able to follow him.

We don't want to connect with our far leg on the far side or with our near leg on the near side (it wouldn't have any effect other than providing a weak frame). Instead, we are going to try connecting to the near side with our far leg and to the far side with our near leg.

This usually takes the form of a lasso with the far leg and a "low leg" with the near leg. There are other ways to achieve these, but the lasso and low leg are standard.

While keeping in mind that you want to avoid a high leg on your opponent's far side, your next objective should be to get at least one foot to frame your opponent's body. It could be the biceps, the shoulder, the stomach, or the hip. As I said, the lasso and the low leg are standard, but there are multiple variations of them, and there are other possibilities outside of them. In the end, the effect is the same.

Managing Distance — Upper Body Frames

When you establish a strong lower body frame, you are pretty safe. The problem is that you usually can’t get it directly. The whole point of outside passing is to get outside the feet in the first place, so it's going to be difficult. This means you have to frame with your arms first before you can get your legs in front of your opponent.

Initially, your opponent would be too far away to frame on, but then they'd get too close to you when your frames are weak, forcing you to use exaggerated high legs to retain your guard, at which point your opponent can start switching sides and making your life miserable.

This means we're dealing with another problem: distance.

In this situation, the objective for the outside passer would be to split or smash the legs together. Either of these breaks the knees-to-chest structure, creating space for the guard pass.

Self-Frames

We can avoid this by using self-frames. A self-frame is simply framing your own body with the goal of maintaining your structure. Self-frames are extremely important for guard retention.

There are many ways to self-frame, but I can't show you them all here. While studying Levi, I saw him use his elbow to frame against the mat and switch sides without compromising his structure. I had never seen that before. It wouldn't be productive to list all the self-framing forms I know.

A good place to start is framing the outside of your thighs, as shown here.

Another self-frame that I use often is grabbing the top of my shins. This keeps my knees close to my chest and prevents early separation.

Play around with self-framing. Do your own research. Look at what the top guys are doing, and try to copy them. Most importantly, do what works for you.

From Self-Framing to Framing on Your Opponent

The problem we had was that we weren't able to frame effectively on our opponent until he was already too close, at which point we were forced to use a strong high leg, which would expose us to side-to-side passing.

Self-framing allows us to maintain our knees-to-chest structure for longer, enabling us to stay strong until our opponent is close enough for us to frame him with a straight-arm frame. This frame allows us to maintain distance, get our feet involved, and position a strong lower body frame, solving the problem of distance.

Connection

Once you establish a strong lower body frame, such as a low leg or a lasso, you can use your arms to connect with your opponent.

A good rule I've been using lately is that if I have a strong lower body frame (i.e., a foot in front of my opponent), then my two arms should be grabbing something. It can be an arm or a leg; the important thing is to immediately connect with your partner.

Look at this example by Levi. He establishes a strong lower body frame and then gets a 2-1 grip on Hulk's far arm. As the situation progresses, Levi changes his grip. Even though he can't do anything significant this time, we can see him using this strategy effectively.

Here's another example, this time against Tye Ruotolo. Here, Levi gets a shallow lasso and looks to get a 2-1 again.

This sequence also ends without Levi establishing any offense, but I wanted to highlight it without showing an actual attack to clarify.

Obviously, you want to use your connections to throw your opponent off balance. Here’s a beautiful example of that:

Here, Levi has a lasso again and grabs Tye’s triceps from behind. He switches to grab the ankle and gets his DLR hook in place. When Tye tries to run away, these connections allow Levi to slow him down and grab the other ankle.

Lastly, here’s an example of Levi effectively using that connection to take his opponent's back:

This was more of a late-stage guard retention into a counterattack, but the same ideas apply.

Although not ideal, Levi has a foot on Lucas’s body and his shin is on Lucas’s shoulder. This allows Levi to use his arms to connect while maintaining a lower body frame.

Levi slowly upgrades his connections until he gets a shoulder pinch on the arm and switches the position of his legs to attack a choi bar. Hulk extends his body to avoid being flipped over, which allows Levi to take his back. That was impressive, but more important is the process that led to that attack: a lower body frame that allowed him to make better connections with his arms.

That's how we solve the connection issue when playing a supine open guard in no-gi jiu-jitsu.

Putting It All Together

I know that was a lot of information. Let's quickly summarize it.

When playing supine guard against a standing opponent looking to create an angle and pass from the outside, which is the biggest problem when playing supine open guard, we need to connect with our opponent to slow him down.

We don't want to use a strong high leg because it would expose us to side-to-side passing. To avoid using a high leg to retain, we want to maintain our knees-to-chest structure for as long as possible before framing our opponent.

We maintain our structure through self-framing. When our opponent tries to close the distance, we keep our knees in place. Once our opponent is close enough, we can frame him, maintaining that space until we can bring a foot in front of him.

Our near leg should connect on the far side, and our far leg should connect on the near side. It can be just one connection or both. This foot usually looks like a lasso or a low leg, but there are different ways to do it.

Once the strong lower body frame is in place, both arms are free to make a strong connection with the opponent, allowing you to switch to an attack.

Finally, here's an example by Lachlan Giles against Kade Ruotolo:

Here, Lachlan self-frames his top leg to maintain his structure. Since Kade is being cautious and isn’t advancing, Lachlan skips getting a strong lower body frame and connects with both arms directly. Once the connection is strong, Lachlan spins under and attacks with a 50/50 heel hook. Hopefully, this example helps you understand the big picture.

So…

As I said at the beginning, I've been working on my supine open guard for a while, and these are the things I've learned. There's certainly more to it than this. For example, I didn’t discuss what to do with your arms other than framing. LIMI BJJ has an excellent YouTube video that goes deeper into this topic. I learned a lot from that video for my own study sessions and practice on the supine guard. That's what indirectly led me to write this article.

Here's the video; make sure to check it out:

Next time you're forced to play supine guard, instead of panicking with high legs, focus on self-framing, establishing one strong lower body frame, and immediately connecting with your arms. Developing this skill will take time, but it’s worth it.

Anyway, that’s everything I had to say. I hope it helps you develop a sick open guard! Have a great day!